29 January 2026

The primary objective of OneBAT is to investigate viral spillovers from bats, specifically targeting lyssaviruses, coronaviruses, and filoviruses harbored by the endangered Miniopterus schreibersii. The knowledge gained is intended for the development of therapeutic and preventive strategies for Disease X, through a One Health approach that addresses both the viruses responsible for zoonoses and the ecology and conservation of their natural reservoir hosts.

At first glance, OneBAT project can sound dense and technical, filled with unfamiliar terms and complex concepts. Yet behind this scientific language lies a simple and urgent goal: understanding how viruses move from animals to humans, and how we can prevent the next global health crisis.

But, to understand where science is heading, it helps to unpack some of the keywords behind this project.

The Main Character: Miniopterus schreibersii

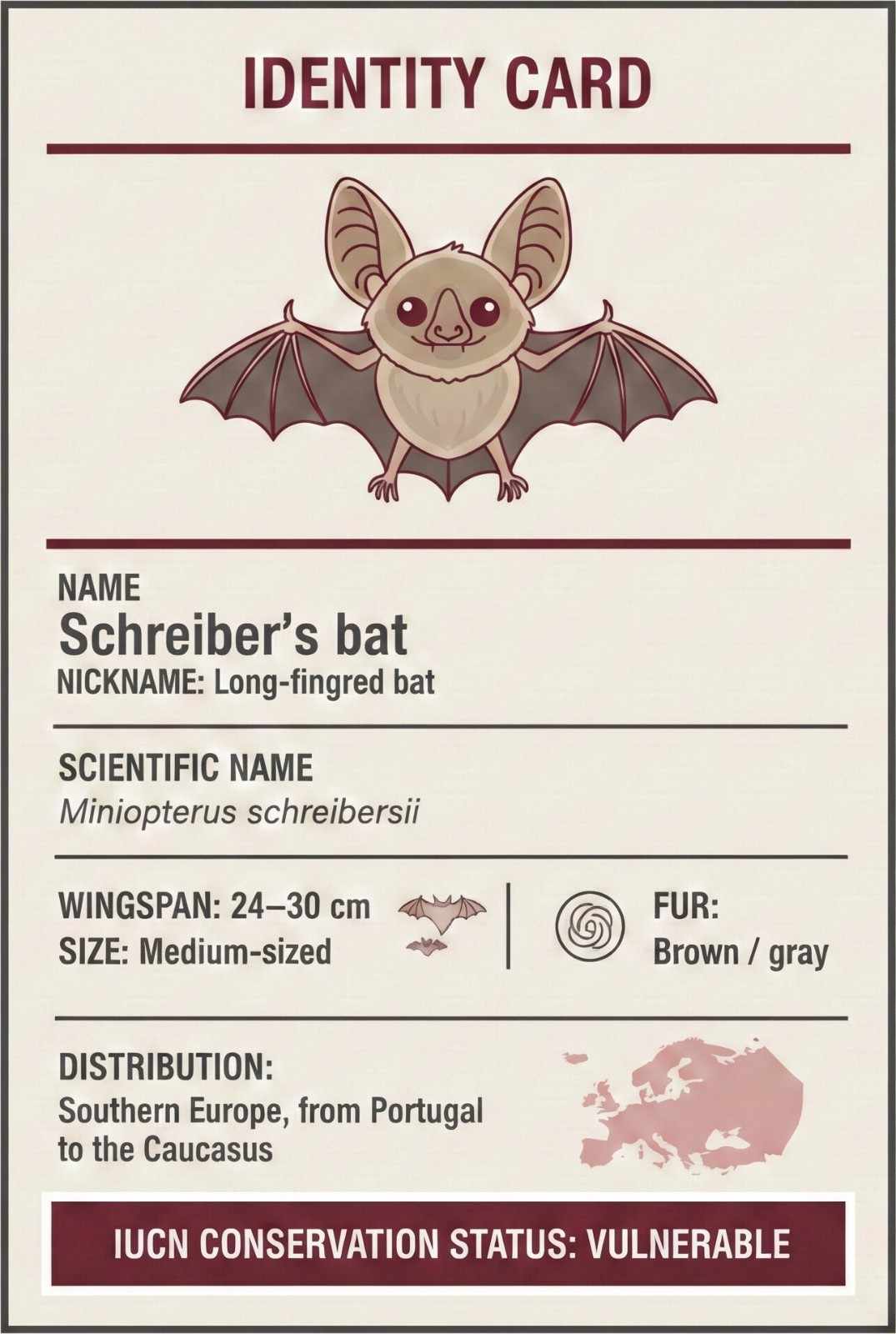

At the center of OneBAT is Miniopterus schreibersii, also known as Schreiber’s bat. It’s widely distributed across southern Europe, where it’s easily recognized by its bent wings. It typically lives in caves and underground shelters, far from human settlements, but migrates seasonally, switching roosts throughout the year. This movements act as a genetic mixing mechanism among bat populations, but they also play a role in how viruses circulate.

Unfortunately, urbanization and human activity have drastically reduced this species’ natural habitats. As a result, M. schreibersii populations are declining, and the species is now classified as vulnerable in IUCN Red List. Habitat loss has also pushed these bats closer to urban areas, increasing contact with humans and domestic animals. This contact can pose a risk, as the species can act as a reservoir host for many types of viruses that are also capable of infecting humans.

This is why monitoring Schreiber’s bat is a key objective of the OneBAT project.

The Role: Reservoir Host

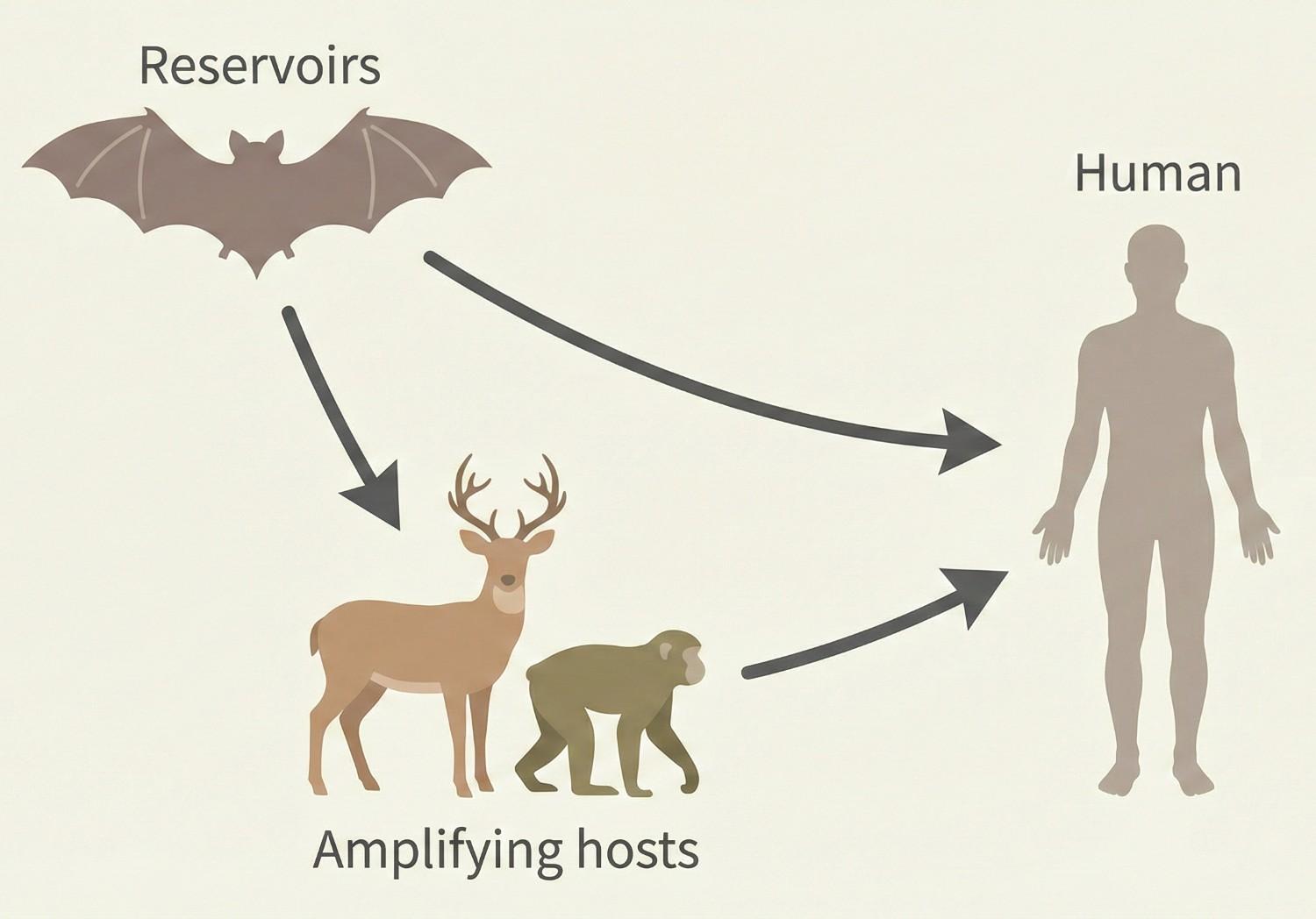

When a living organism harbors a pathogen, allowing it to live, grow, and reproduce, it is known as a reservoir host. It serves as a source from which the infectious agent can be transmitted to other hosts, leading to the spread of infection and disease.

From an evolutionary perspective, viruses do not “aim” to cause disease. Their primary goal is to replicate and spread. Severely debilitating or killing the host can be counterproductive, as it limits contact with others and reduces opportunities for transmission. Over time, many viruses evolve toward a form of balance with their natural hosts, becoming less harmful while continuing to circulate. However, even if a reservoir host shows no symptoms, it can still transmit the virus to other, more susceptible species, leading to a spillover event.

This is why understanding the role of reservoir hosts is essential for predicting and preventing disease outbreaks, especially those involving bats.

The Problem: Spillover

Spillover refers to the transmission of a virus from one reservoir species to a new host species, in which it can die or adapt and possibly trigger an epidemic. This definition was provided by experts at Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale delle Venezie, the coordinating institution of the OneBAT project.

Because the new host is not adapted to the virus, the outcome is unpredictable. Some viral variants may replicate more efficiently or evade immune defenses more successfully, increasing the likelihood of infection. When humans are involved, this process can give rise to zoonoses.

If the new host can in turn transmit the virus to others of the same species, or if contact between reservoir species and susceptible hosts increases, an epidemic may arise.

Understanding spillover events is crucial in predicting and preventing viral emergencies, especially those involving bats as reservoir species.

The Risk: Zoonosis

The World Health Organization defines Zoonosis as to any disease or infection that is naturally transmissible from vertebrate animals to humans. Transmission can occur in several ways:

- Direct contact, such as exposure to skin, fur, blood, or secretions, as in the case of rabies, a disease caused by a Lyssavirus and transmitted through saliva;

- Indirect transmission, via vectors like mosquitoes that feed on infected animals and humans, or through contaminated food and water.

Most emerging infections identified in recent decades have been caused by viruses previously unknown to humans and initially confined to animal species. For this reason, understanding zoonotic diseases is crucial for public health, as it allows us to anticipate and manage potential health threats originating from animals, including bats.

The Villains: Lyssaviruses, Filoviruses, Coronaviruses

OneBAT focuses on three major viral families:

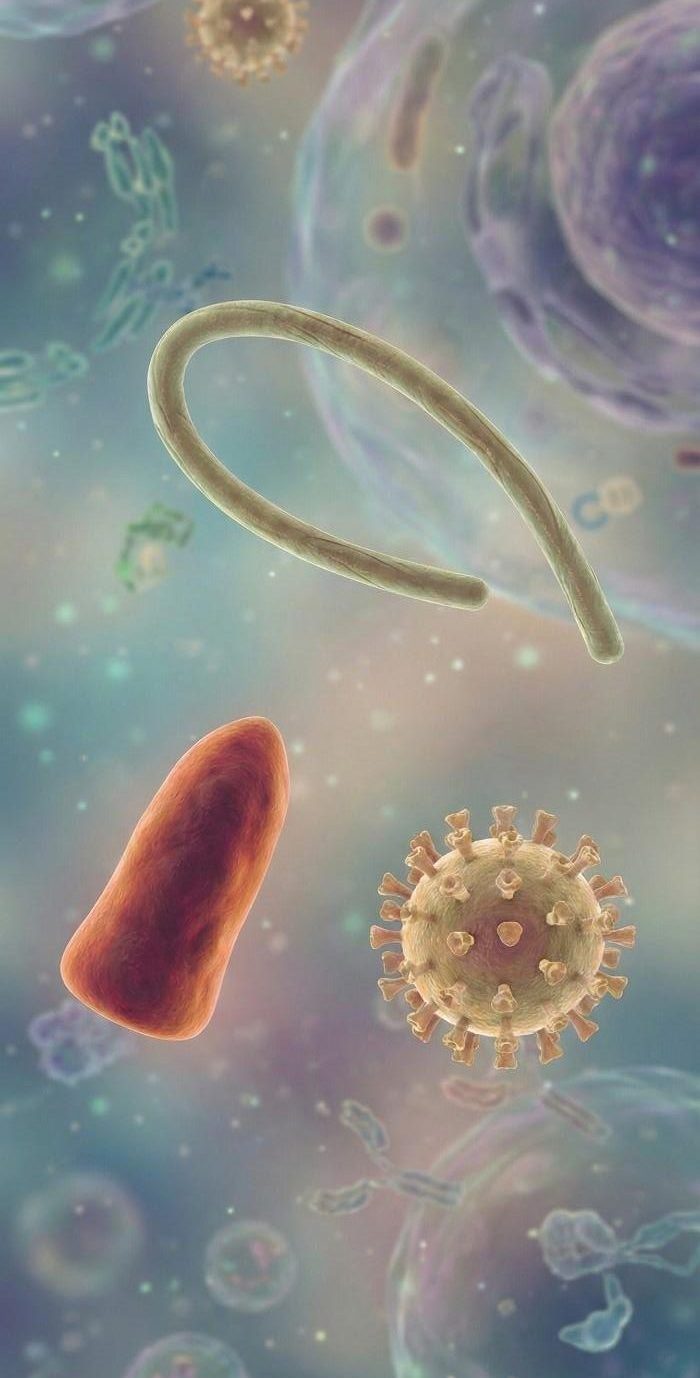

- Lyssaviruses, from Lyssa, the ancient Greek goddess of rage and fury, include Rabies virus, a bullet-shaped virus responsible for a widespread zoonotic disease affecting many mammals, particularly canids and bats. They primarily target the central nervous system, causing symptoms such as aggression, excessive salivation, and hydrophobia, before reaching the salivary glands and enabling transmission through bites.

- Filoviruses are filament-like shape viruses, including Ebola virus, which has caused severe hemorrhagic fever outbreaks in several African countries since the 1970s. While non-human primates have often been identified as sources of human infection, bats are considered the natural reservoir hosts of these viruses.

- Coronaviruses are spherical viruses with crown-like surface spikes. This large viral family infects a wide range of animals and commonly causes respiratory or gastrointestinal diseases. More than 60 distinct coronaviruses have been identified in bats, some genetically related to human strains. It’s suggesting that spillover events often begin in bats, sometimes involving intermediate hosts before reaching humans. In some cases, as with SARS-CoV-2, these events have led to large-scale epidemics and even global pandemics.

The viruses studied within OneBAT circulate naturally in bat populations and share genetic similarities with human ones, yet many aspects of their biology remain poorly understood. In particular, their zoonotic potential, especially for bat coronaviruses and filoviruses, has not been fully characterized, and there is still limited information on the effectiveness of existing vaccines and therapeutic tools in reducing the risk of infection.

For these reasons, comprehensive monitoring and understanding of emerging bat-related viruses are crucial for mitigating future health threats. Past epidemics have repeatedly shown that human health is closely linked to animal health and to the shared environment in which all species coexist, including the risk posed by a potential Disease X.

The Solution: One Health

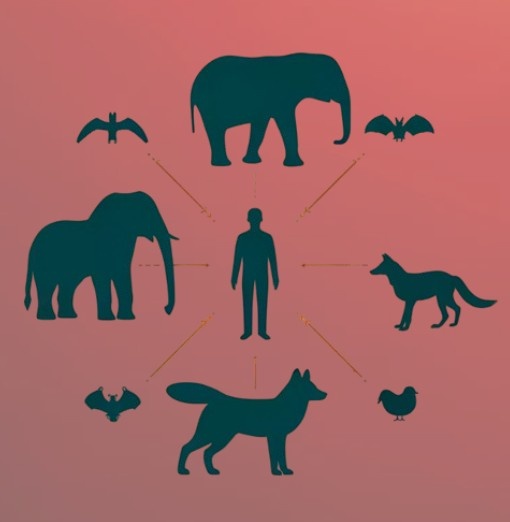

One Health is an integrated, unifying approach that aims to sustainably balance and optimize the health of people, animals, and ecosystems. The world we live in is shared, and future health emergencies cannot be prevented or addressed without acknowledging the complex interconnections between these three domains.

- When human activities degrade habitats and consume natural resources, ecosystems are weakened.

- When wildlife populations decline, their ecological roles are disrupted, with consequences that can extend even into urban environments.

- When contact between humans and wild animals increases, so do the risks of spillover, zoonoses, and epidemics.

The full name of the project, One Health Approach to Understand, Predict, and Prevent Viral Emergencies from Bats, reflects this perspective. This “One World, One Health” approach aligns with global efforts to be prepared for health emergencies.

Join us in understanding how the One Health approach is essential in bridging the gaps between human, animal, and environmental health.