26 January 2026

Since 2013, Western Europe has been officially free from endemic rabies (RABV). However, the scientific community remains vigilant: other members of the Lyssavirus family are still circulating among wildlife, particularly in bat populations. These “cousins” are related to RABV but divergent: over time, they have evolved in different directions, accumulating genetic differences affect the efficacy of current vaccines and treatments.

While rare, these viruses can occasionally jump from one species to another thanks to a phenomenon known as spillover. A high-profile example occurred in Arezzo, Italy, in June 2020, when a domestic cat was infected by the West Caucasian bat virus (WCBV).

This event served as a stark reminder that pathogens from wildlife can cross the species barrier, much like the virus responsible for the global pandemic the world was facing at that same time.

WHO (2024), image by who.int

Project OneBAT: Strengthening European Preparedness

To better anticipate these threats, the European project OneBAT was launched. Researchers from the consortium coming from Italy, Spain, France, Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary, and Serbia, joined forces to study two specific divergent lyssaviruses,also involving colleagues from Bulgaria, Romania and Serbia:

• West Caucasian bat virus

• Lleida bat lyssavirus

Both viruses are primarily found in Miniopterus schreibersii, an insectivorous bat species common in Southern European caves. While it can host pathogens of public health concern, it is also a vulnerable species on the IUCN Red List and is strictly protected under both national and European conservation laws. As human activity destroys their natural habitats, these bats are increasingly found in urban areas, increasing the potential for contact with humans and domestic animals.

Study Results: How Widespread Are These Viruses?

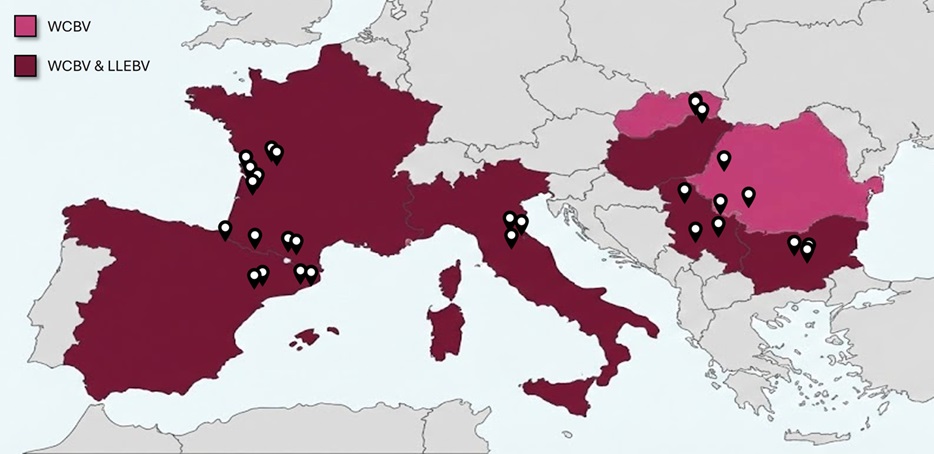

Experts from Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale delle Venezie (IZSVe) and Institut Pasteur tested nearly 600 bats’s sera to investigate their exposure to the target viruses. Sera were collected from 29 locations in eight countries thanks to the hard work of IZSVe, the University of Pecs, the University of Barcellona, the France Nature Environnement of Nouvelle-Aquitaine, the National Institute of the Republic of Serbia, the Centre for Bat Research and Conservation of Romania and the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences. Serological tests revealed a wide geographic spread: West Caucasian bat virus (WCBV) was detected in 24 sites spanning all of them, while Lleida bat lyssavirus (LLEBV)was identified in 11 sites across six.

Notably, evidence of exposure to both viruses was detected in some individual bats.

Based on these results, research concluded that Miniopterus schreibersii likely serves as reservoir for these viruses, allowing them to persist and circulate usually without causing symptoms.

AI generated

Pathogenicity: How Dangerous Are They?

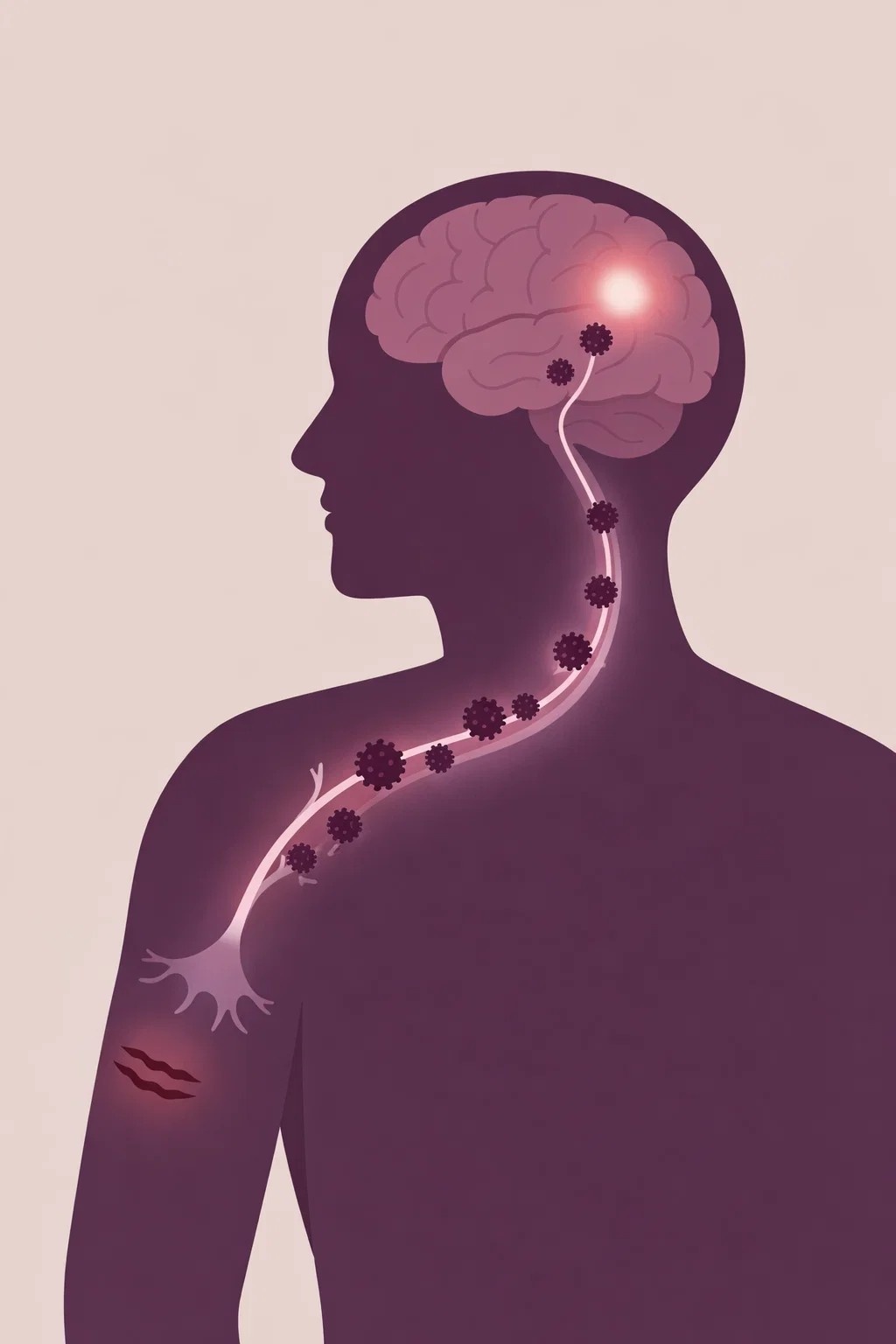

When Lyssavirus jump to other hosts (such as humans) via a bite, they target the central nervous system, causing acute encephalitis, leading to severe neurological symptoms.

In the same study, researchers also tested their pathogenicity, the ability to cause disease, in animal models, and identified marked differences between them:

- West Caucasian bat virus: Fully capable of causing a rabies-like illness in hamsters, with lethal outcome.

- Lleida bat lyssavirus: at the tested dose, proven lethal for other Lyssaviruses, cannot establish infection in hamsters through intramuscular injection, the classic transmission routes associated with rabies.

Understanding these viral “cousins” is essential for determining the actual risk they pose to public health. By building this knowledge today, we can prevent outbreaks caused by lesser-known pathogens in the future.

This research highlights that protecting wildlife habitats is not just an environmental issue: it is a public health necessity. When we safeguard natural ecosystems, we reduce the chance of spillover events and protect both human and animal lives.